|

|

|

|

|

|

Jamie Bishton | Dance

Presented at the Joyce SoHo, September 22, 2002. Choreography by Jamie Bishton. "41" (2002); "Tr(us)t" (2001); "You think you really know me" (2002); "From a Life Together" (2002); "Things That Cannot Be Painted" version 2 (2002).

Web for Jamie Bishton | Dance: www.jamiebishtondance.com Web for Joyce Soho: www.joyce.org/soho.html

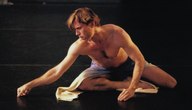

Photos of Jamie Bishton courtesy of Jamie Bishton

Review by Robert Abrams

|

Review by Roberta E. Zlokower |

|---|

|

The choreography presented tonight expressed a single movement idea. This idea is modern dance with a flowing quality. The presentation was effective as inquiry because it presented this single idea with variations that each leaned in the direction of a different form of dance. These influences included African, Vintage/Standard, Smooth, and Ballet. The evening included five dances. "41" Jamie Bishton's dancing was both graceful and controlled. He danced with the patina of Gene Kelly. This perfectly fit the movie music by Max Steiner. Halfway into the piece, the choreography turned serious and stately. This piece made active use of a video projection in the background with snapshots of Jamie's family and friends. Sometimes the dance made postural references to the photos projected in the background, and often it did not. Overall, the best way to describe Mr. Bishton's bearing in this dance is to say that he was a shirtless Clark Kent and leave it at that. "Tr(us)t" Ana Gonzalez and Paul Matteson flowed around each other. There was a good relation between the music and the dance. There was a necessary and dependent relation between the dance partners. This is often missing in traditional modern and ballet stage choreography, so it was refreshing to see that Mr. Bishton firmly understands the importance of this principle: making the movements of two dancers dependent on each other, rather than just incidental to each other, can bring out the potential in both the choreography and of the dancers. There was a slightly African feel to some of the movements. Ana and Paul demonstrated clean and appealing execution of the lifts. There was interesting exploration of the story within the movement type, without totally abandoning the typical narrativeless approach to choreography that is often characteristic of Modern dance. This was Modern dance you will probably enjoy watching even if you usually detest Modern dance. "You think you really know me" This dance was waltz-like, but with a Vintage feel to it. The dance expressed the character of the movement being explored. The chandelier used as stage dressing was a good fit with the movement. The choreography suffered from a problem often found in Standard. The movement is interesting, but to really express its beauty fully, it needs more dancers on the floor to fill the stage properly. I have four suggestions for where Mr. Bishton might try taking this piece next. 1) The dance needs a comparison group: a dance in the same style, but with a partner. These two dances would be performed one after the other. The audience would then be given a short survey with a combination of closed and open ended questions. Ideally, the research should be designed with a split sample: half of the respondents would see the dances in the AB order, and the other half in the BA order. Why settle for dance as entertainment when you can also turn it into a research project? 2) Do the above experiment, but vary the audience by taking the dance company back to the 1890s. Okay, this research design is currently impossible, but a variation of it is possible. The fundamental assumption being tested here is that different people resonate to different rhythms. This could plausibly explain why I tended to prefer the pieces with African or other decidedly percussive music, and less so the more melodic ballet influenced pieces. The problem with traditional dance criticism, from a researcher's perspective, is that traditional dance criticism has an N of 1. A larger sample would give us a better sense of whether the assumption is valid. Even if one can't perform in 1892, one could identify a large population, and then randomly select a stratified sample from that population based upon their musical preferences. One would then test the results of the survey to see if there is a relationship between people's understanding of the dance and their musical preferences. 3) As above, but extend the experiment by starting with one dancer, moving to two on stage, then four, and finally eight so that the energy of the choreography builds over time. 4) Leave the piece as is, but try adding more and longer moments of stillness to make the movement more apparent. These moments are already there, both in terms of posture and expression, but they were so short that one couldn't fully appreciate them. Ordinarily, Modern dance has too much stillness, but this is one case where just a dash of the Modern dance tradition would bump both the choreography and the dancing from good to inspired. The audience would be able to better appreciate the still moments, which would then give the movement a stronger frame, thus helping the audience to better understand those movements. "From a life together" This piece was Ballroom-esque. It was clearly in the Smooth tradition, given the amount of open work. There was a good match of the movement with the intensity of music at the end of the piece, but sometimes there was a mismatch: sometimes the choreography didn't know what to do with fast tempos. On the other hand, partnership turn combinations were used expertly to express the drama in the story being told. Anyone familiar with the Ballroom scene would have recognized the sort of soap-opera-ish falling apart and coming together that is quite common in professional partnership dance. A couple of longer Viennese passages might have tightened up the overall choreography. "Things That Cannot Be Painted, version 2" This piece had turn combinations that echoed "From a life together". "Things that cannot be painted, version 2" showed that Mr. Bishton can respond well to energetic music. That is, after all, one of the benefits of seeing multiple works by the same choreographer presented in the same evening: one gets a fuller sense of the depths of his capabilities, which in this case are both deep and capable. This piece was so energetic, it set the stage on fire. Literally and figuratively. Mid-way through the dance, a dancer bumped into a stage light set on the floor. The light fell over and started to burn a hole in the floor, sending up an increasingly visible amount of smoke. A minute or two later, a dancer had the presence of mind to drop out of the dance and right the light, yet managing to stay in character while doing so. This was reminiscent of the way that Cesar returned Nicola's earring in character in a recent performance of Swango. Nicola's earring was not supposed to fall off, but it did, and leaving it on the floor might have been hazardous to the dancers. Cesar picked up the earring and returned it to Nicola, making it look like it was supposed to be part of the show. Mr. Bishton's company demonstrated their professionalism in keeping the show moving all while preventing Joyce Soho from burning to the ground - which we do not want to see happen because it is a very attractive space for dance performances. The use of varied numbers of dancers in motion at any given time was well done. All in all, "Things that cannot be painted, version 2" was stunning choreography which was performed with both skill and passion. The evening was worth attending. There was more than enough individual accomplishment and choreographic complexity to make the whole show worth a second viewing.

|

"41": Dancer, Jamie Bishton; Music by Max Steiner, 1941. On the occasion of Jamie Bishton's 41st Birthday, he performs in a solo that has evolved from the premiere work, first performed last year. Coincidentally, the score is composed by Max Steiner ("Gone with the Wind") to compliment this autobiographical work, which is danced against a backdrop of photos, contributed by family and friends. Bishton dances in images of feelings, evoked by the connection with these photos. In a skirt-like costume, Bishton extrapolates the emotions from Max Steiner film scores and from his memories of experiences with those in the ever-changing photos, which add texture and context to his performance. Arms outreached, spinning and leaping, Bishton creates an engaging extension to the fascinating video backdrop. Several dances in this evening's varied collection have been enhanced by the use of a backdrop, a large screen, upon which a video collection of images, or one image, has been projected. Kudos to Duy Linh Tu, who has collaborated with Bishton in all the video installations. "Tr(us)t": Dancers, Ana Gonzalez, Paul Matteson; Music by Eric Oberthaler and Mark Reveley. Bishton sends the composers videos of the performances, danced to temporary music, and then they compose music, tailor-made to the individual dancers, and to their interpretations of this piece. The composers have never personally attended a live performance of their music, as their sole contact is via Bishton's videos. This is an ever-changing dance composition. To electronic music, which pulsates and builds to resounding crescendos, the dancers intertwine, with romantic connections and stage-extending leaps and embraces. Costumes were natural in color and texture, with dancers in flowing movement and design.

"You think you really know me": Dancer, Stephanie Liapsis: Music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Sonata (Trio) in B flat, K.266). Stephanie Liapsis dances in these final three pieces with unfailing energy and amazing grace. She is glowing and dynamic, as she is tireless and totally in control of her balance and partnering. She is capable of assuming a variety of moods, an Odette-Odile ("Swan Lake"), in this piece and in "From a Life Together", in which she metamorphoses from ingénue to sibling rival, with perfect balance of moods and movement. Liapsis epitomizes the joy of discovering a growing sense of femininity, with outstretched arms and arabesques, against a video backdrop of an ocean painting, with the dancer positioned beneath an elegant chandelier, dancing in remembrance of the warmth and ardor of sun and sand.

"From a Life Together": Dancers, Jamie Bishton and Stephanie Liapsis: Music by Fanny-Mendelssohn-Hansel (String Quartet in E flat major). This is a piece about the rivalry between Felix and Fanny Mendelssohn, caused by a controlling father, who extensively educated both son and daughter in music, but only allowed the son to publish his compositions. Upon the death of their father, Felix allowed Fanny's compositions to be published. In black and white, Chiaroscuro, Liapsis turns from former ingénue ("You think you really know me") to cunning, jealous sister, a love-hate, focused, balanced, passionate dancer, one with purpose and wild, sensuous form. Liapsis and Bishton use the full extent of the stage, in elegant costumes, with an abstract black and white video projection as backdrop, to act out their tales of creative expression and fulfillment of dreams, of conquest and control, of forgiveness and fortitude. This is a lengthy piece, with mirror images, staccato and dynamic movement, percussive arm extensions and releases, and interlocking duos, as Bishton and Liapsis combine a variety of emotions and evolving choreography to unfold this historical tale. "Things That Cannot Be Painted" version 2: Dancers, Tricia Brouk, Stephanie Liapsis, Ashleigh Leite, Meg Moore, Rebecca Warner, Seth Stewart Williams, and Lisa Wheeler: Music by Greg Hale Jones, "She Began to Lie". Mr. Jones' recordings of cotton field workers and state prisoners were synopsized into this new song, performed by the above septet. This piece is a visual dessert, like baked meringue or a fresh snowfall, seven dancers in white, flowing, pajama-like costumes. The floor-lighting and shadows are dramatic, the music and sets stark, and the backdrop now a purposeful white wall. The electronic, rhythmic drums are set against the innocent, white, flowing costumes, which enhance the large, stark walls and lighting effects, with ever-present shadows and .percussive sounds. Full-body lifts, elongated arms and legs, and outreached expressions and emotional need are ever-present during this work, which was originally commissioned by Barnard College.

|

|

|

|