|

|

|

|

|

|

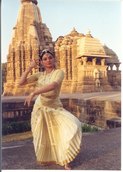

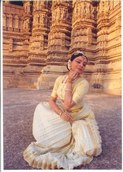

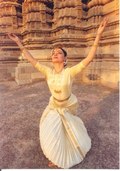

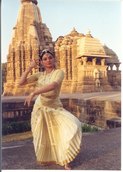

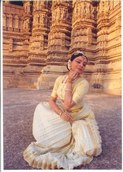

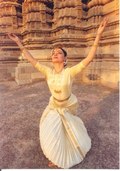

MALAVIKA SARUKKAI: a quintessential performer of Indian classical dance.by Rajika Puri

November 24, 2002

Malavika Sarukkai, who performed at Symphony Space on November 15th under the aegis of the World Music Institute, is one of India's foremost exponents of Bharatanatyam, the dance form that originated in the temples of south India. Indian dance lovers go to her performances with high expectations. They are rarely disappointed. With her beautiful lines, deeply convincing mime, and exquisite taste in music, costume, and presentation, she transports even newcomers to Indian dance into a world of beauty, sensuality, and timeless human emotions richly infused with a sense of the sacred. Since her debut at Lincoln Center's Alice Tully Hall, Malavika has both grown as an artist herself and contributed to the growth of Bharatanatyam as a theatrical performance art. In recent years she not only gives performances of the conventional Bharatanatyam repertoire, but presents choreographic works which follow a specific theme, such as the one she brought to Symphony Space entitled Khajuraho-Temples of the Sacred and the Secular. The temples of Khajuraho are actually in north India. They are perhaps notorious for their sculptures of couples in the act of making love which, along with representations of voluptuous women standing in a wonderful variety of poses - gazing into a hand-held mirror, removing a scorpion from the back, a thorn from a foot - are the backbone of Indian tourist posters. Built around the end of the first millennium, this temple complex is the venue of an annual dance festival, and featured as backdrop to Mira Nair's film Kamasutra. In her Khajuraho, Malavika "pays homage to the temple as the sacred site of the origin of classical dance", particularly these temples "which resonate with the sacred even as they celebrate the secular". She starts with a section inspired by the still center at the heart of the temple where male and female principles come together in creative union and from which space expands outward in all directions. At the end of the ninety minute work, her music slows down, as do her movements, until she gathers herself into that still, sacred, center again. While beginning and end are expressed in abstract, rhythmic, movement based on the codified vocabulary of Bharatanatyam which she adapts to express her ideas, the two central sections employ the highlight of this dance form - an elaborate body language called 'abhinaya'. Hand gestures, facial expressions and evocative stances are used to convey dramatic meaning, attempting to get at the emotional heart of the sung poetry which accompanies the dance. The first of the central sections deals with love, desire, and sensuous beauty. With every movement Malavika expresses a range of moods, from the playful - as when the god of love, Kama, showers us with his arrows of flowers, to the passionate - like when two lovers tremble as they lean forward to embrace, and a shiver of ecstasy runs through the audience. The second central section refers to the battle friezes surrounding some of the Khajuraho temples, and reminds us that many of these temples were built by kings and queens in gratitude for victory at war. While Malavika ends with a magnificent enactment of a military procession leaving a city, she first depicts a mother and then a wife taking leave of a warrior king as he sets out for battle. Here, Malavika's abhinaya focuses on the conflicting emotions of pride and anxiety as two women face the possibility of future glory at the price of never seeing their loved one again. At its core abhinaya contains the idea of conveying meaning by suggestion. The great Bharatanatyam dancers, who performed at a conversational distance, were able to hint at the subtlest of ideas by raising an eye-brow, or quivering a lip. Since Indian classical dance moved to the modern theatrical stage with audience members sometimes over a hundred feet away, many performers have taken to exaggerating their mime. This often pleases western audiences, too, perhaps because they are easier able to understand the emphatic style of acting. Malavika's response to the new venue for classical dance is not so much to exaggerate her movements as to use her whole body to convey them in the subtlest of ways. A hallmark of her mastery over abhinaya is the ability to capture a stance, and infuse it with the essence of an emotion she wishes to evoke. Three moments stand out. First, when the widowed queen-mother draws herself up as her son bends down to take her blessing. The old woman stands proud and regal, but something inside her seems to break. Second, when the king walks around the room carrying his infant son, his young wife joins him leaning against his left arm, a moving picture of conjugal bliss, captured in just a few graceful strokes. The last is when the young queen closes the large doors after him, and then bows her head against her two hands still resting against the doors. Her barely expressed pain feels intolerable. The concept of Khajuraho was developed jointly with Saroja Kamakshi, Malavika's longtime collaborator and manager, who also speaks the beautifully thought out explanations which accompany the danced demonstrations that precede each section. We are thus always kept privy to what the dancer wishes to convey, and can enter into the spirit of her intent. The musicians, too, punctuate the narrative with unusual sounds from their instruments. Violinist N. Sigamani not only captures the essence of a mood with his improvisations on a raga (Indian musical mode) but, to underline a gesture, he often draws a wail from his instrument that is rare in south Indian classical music. Similarly, drummer P.K. Ranganathan is not only masterly with the complex rhythms of Malavika's choreography but at times produces an almost speech-like timbre with his mrdangam. Though spoken of in English as a 'dance' form, Bharatanatyam is considered the quintessence of ancient Indian theatre as described in Sanskrit texts like the Natyasastra attributed to the legendary sage Bharata (and thus was given this name in the 1930's when the dance form was brought out of the temple and performed on the urban stage). Exponents who do equal justice to music, poetry, rhythmic movement, and dramatic mime - especially when dealing with non-traditional themes - are rare. Anyone watching Khajuraho cannot but fail to recognize that Malavika is one of them. She is herself a quintessential performer of this quintessential Indian art.

|

|

|