|

|

|

|

|

|

In Santa Fe, New Mexico, the hoopla surrounding the annual opera season at The Santa Fe Opera is like football season elsewhere. First come well-timed announcements from the press office about what the opera lineup will be, and which star players have been contracted. Then comes the rush for tickets for all five operas, which are purchased across the country and around the world, and finally, the tailgate parties, gowns, tuxes, and sequined denim that herald opening night. The draw for opera audiences is the singing and the music, but increasingly there is a demand for and an enthusiastic response to believable, confident acting, sophisticated stagecraft and– of greatest interest here, movement and dance. La Fanciulla del West (The Girl of the Golden West), is, simply stated, Puccini’s little-performed operatic paean to the redemptive power of love. In seeing The Santa Fe Opera's opening night performance of it on July 1, it was an excellent theme for troubled times, and a good choice for a city where cowboy hats and boots abound. The story– which is sometimes so silly that it elicits unintended laughter from the audience– is about a woman, Minnie (Patricia Racette), who runs the Polka saloon frequented by miners in the days of the California Gold Rush. The men suffer from homesickness, and right below the macho surface of their gambling, cussing, brawling veneers, are longing hearts. Minnie gives them Bible classes and is the object of everyone’s love, especially Jack Rance (Mark Delavan), the town sheriff. Enter, in disguise as Dick Johnson (Gwyn Hughes Jones), the infamous bandit Ramirrez. Minnie, who met him once before, is smitten by him, and the rest of the plot revolves around Minnie’s love for the bandit, Rance’s envious hatred of him, and the men going after Ramirrez, shooting him, and preparing to hang him. In the end, Minnie appears, and her appeal to the heart of the men saves her beloved from death and opens the door for redemption and forgiveness. Now, to the movement and dance. Sadly, there is little use of the human body in any meaningful way. The libretto is liberally sprinkled with references to dance, waltz, and more dance, but the clunky and aimless movement of the singers on stage in cramped sets makes one wonder what the director, choreographer, and fight director were thinking. Minnie and Ramirrez use broad, exaggerated gestures and clutch at the walls like actors in a silent movie. The men, in their loneliness, partner up with each other in the dancehall. But instead of highlighting the pathos or humor of the awkward dance, it is tossed in for a few moments, and then forgotten. The words speak about the first time Ramirrez and Minnie danced together, when she felt love and he knew joy and peace in his heart, but, alas, they sing to each other statically from a distance, rather than sharing the same space of memory and emotion. A barroom brawl is stereotypical and unconvincing, and many of the punches land in the credibility gap. The men cross the stage with their guns while pursuing Ramirrez, but the guns are handled like weightless toy props. And Ramirrez, who is shot at and prepared for hanging, flops around the stage and lands like a lump, which is decidedly unflattering for his round body type. The audience needs to see his charisma and bad boy appeal. Luckily, the resplendent singing and the music soar, and connect to the enthusiastic audience. But the connection that should take place physically among the principals is oddly ignored, underused, or not organic to the performers. In the third act, the men stand on risers, which resonate as they stomp with their boots. The sound and the visual of all the men create tension and pressure as they prepare to kill Ramirrez. This would have been the perfect time to choreograph an escalating tension, with the insistent and building stomping sounds. But it ceased as quickly as it started. The words of the pursuers are that they will “teach you (Ramirrez) the last dance,” but what dance? The dance theme throughout is sadly underutilized or ignored. Ironically, the strongest visual moment is when the men stand still, lined up, looking like a tableau, at the end. It would have been wonderful to contrast this moment of stillness with the vigor and pathos and beauty of dance and movement throughout. But things get much better in The Santa Fe Opera's next production – Mozart’s brilliant Don Giovanni that opened on July 2. The story of one of opera’s most seductive, heartless male characters is well known. Don Giovanni (Daniel Okulich) lives for conquest and bedding, with false promises of wedding. His servant, Leporello (Kyle Ketelsen), is forced to keep a list of the seduced, who number in the thousands. Don G kills the irate father of one of his conquests, and, at the end, the statue of the deceased comes to life and to dinner and drags the unrepentant womanizer off to hell. From the first moment on the bare stage, when bewigged servants, their backs to the audience, look out at and are outlined by Santa Fe’s multi-hued setting sun, we know we are in sure directorial hands with Ron Daniels. And for three hours, he and choreographer Nicola Bowie don’t disappoint. There is no dance, per se, in the opera, but the picture-perfect casting and the awareness of space and the movement of singers through space, makes the production soar. Don G is charismatic, dashing, and dastardly. His reluctant servant, Leporello, is deft, agile, and has a bent for the comic gesture. The three female principals, all victims of Don G’s lecherous narcissism are, by turns, pathetic, admirable, vengeful, addicted to seduction, co-dependent, and deft. They know what they are feeling, their movements express that feeling, and they, like the sparse décor, male counterparts, lighting, and costuming, make a unified, satisfying whole. Thanks to Daniels and Bowie, this production is a textbook lesson in engaging physicality, built, in large measure, by the economics of effective stage movement, and the awareness that each gesture in space is a statement, an underscoring, a comment. Each movement has a purpose and a rhythm: by turns fast, slow, grandiose, understated, beckoning, challenging, aggressive, passive, limp, rigid, joyous, sad, tortured, triumphant, direct, indirect, heavy, light, submissive, superior, playful. The singers strut, swagger, bow low, swirl, lie down, kneel, leap, collapse, sit, mimic, pose, using all levels to express their emotional lives. They also connect to each other physically– they touch, hold hands, caress, console, fondle, swat, and engage. Even when they are not making physical connect, they connect emotionally with each other as they try to manipulate, seduce, flee, flatter, pacify, taunt, and tease. The moments of intense activity alternate with stillness, which comes from inside. The attention to detail and physical control results in an almost balletic performance, albeit one with hardly any actual dance. With these two performances under our operatic belt, we look forward to seeing how the directors, choreographers, and fight directors use movement in the other three of this season’s offerings. Remaining PerformancesLa Fanciulla del West: July 15 and August 2,8,13,17,23,27 Don Giovanni: July 13,22 and August 1,6,10,15,20,26

The cast of "La Fanciulla del West" (Girl of the Golden West). Photo © & courtesy of Ken Howard |

|

Patricia Racette (Minnie) and Mark Delavan (Jack rance) in "La Fanciulla del West" (Girl of the Golden West). Photo © & courtesy of Ken Howard |

|

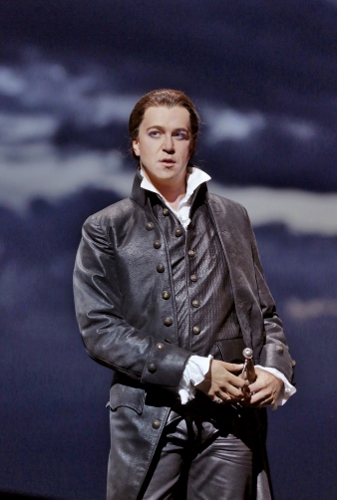

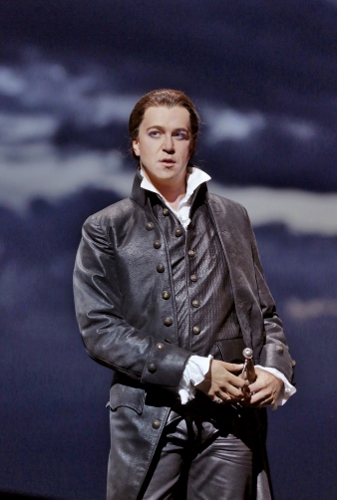

Gwyn Hughes Jones (Dick Johnson) and Patricia Racette (Minnie) in "La Fanciulla del West" (Girl of the Golden West). Photo © & courtesy of Ken Howard |

|

The cast in "La Fanciulla del West" (Girl of the Golden West). Photo © & courtesy of Ken Howard |

|

Daniel Okulitch in the title role of "Don Giovanni." Photo © & courtesy of Ken Howard |

|

Rhian Lois (Zerlina) and Ensemble Cast in "Don Giovanni." Photo © & courtesy of Ken Howard |

|

Keri Alkema (Donna Elivra) and Kyle Kettelson (Leporello) in "Don Giovanni." Photo © & courtesy of Ken Howard |

|

Keri Alkema (Donna Elivra) in "Don Giovanni." Photo © & courtesy of Ken Howard |

|

Leah Crocetto (Donna Anna) in "Don Giovanni." Photo © & courtesy of Ken Howard |

|

|

|