|

|

|

|

|

|

As part of their three-week New York City stay, the Kirov Ballet, based in St. Petersburg, Russia, put on an evening of works all by American-German postmodern choreographer William Forsythe. This was a daring move by the company, which is known for its classical programs. Indeed, many audience members seemed confused, and some left well before the end. But those of us who have longed for some time to see a full program of work by the choreographer who felt forced to leave the U.S. for Europe, where his ideas are more accepted, whose dances are not often performed here, are very grateful. The running theme of these ballets, brilliantly brought to life by the premiere Russian company, was Forsythe's questioning the boundaries of performance and ballet. The first dance of the night was "Steptext," a ballet from 1985 for four dancers set to Bach's Partita Number 2 in D Minor. The curtain came up to reveal one dancer onstage, moving without music. It appeared that he was just warming up – he was wearing a basic black top and tights — but of course before an audience, and on a proscenium stage. The doors to the lobby remained opened and the audience lights fully on, then slowly dimmed as the music began and a female dancer, the striking, statuesque Ekaterina Kondaurova, came onstage and began a pas de deux with the man. As with much of Forsythe's passages, this pas de deux was fraught with emotion, with forcefulness, even understated violence. They danced, then parted, and another set of dancers entered, all the while the audience lights coming on slowly, slowly building to a bright crescendo until the audience could fully see each other and the dancers could see the audience, then would slowly dim again until the audience area was "properly" dark and only the stage lit. The audience seemed confused and some questioned whether this lighting was intentional. It was obvious that it was, though, because of the dimming at precise intervals and the ease with which the lights came on and off. Much of the movement in this piece contrasted fluidity and freedom with geometry and order, as some dancers would exhibit beautifully flowing upper body movement, the arms — particularly those of Alexander Sergeev — at times seeming almost like liquid, while others would make square-like shapes with their limbs. As one pair of dancers flew across the stage like birds (or, like typical ballet dancers), another couple stood still, moving only their arms, each standing on a corner edge of the stage, while regarding each other straight-on, and making boxed patterns as if to frame the moving dancers. The second ballet was "Approximate Sonata," from 1996, consisting of five duets with some spoken word mixed in, and continuing the theme of the boundaries of performance. It began with one male dancer walking slowly toward the audience, screwing up his eyes and puffing his cheeks so as to comically distort his face. He looked like a bloated doll at points. He began talking, seemingly addressing the audience, but since he spoke in Russian I couldn't understand what he was saying. Soon, a female dancer joined him for a duet, which was followed by more duets. During one pas de deux, two dancers argued back and forth with each other, presumably over the choreography or the proper execution of a step. They attempted a difficult lift and the man nearly dropped the woman. "Ugh," he burst out before issuing instructions to her. They "practiced" some more, and the piece ended non-dramatically with that man deciding to sit it out and just watch his female partner, the mesmerizing Elena Sheshina, as she practiced her part of their routine, repeating a phrase over and over again until she got it to her liking, working out each phrase, checking her form in an imaginary mirror, deciding what looked best. The curtains slowly went down in the midst of her practice and, watching her was so surprisingly spellbinding, you did not want that velvet to hit the floor. Next was "The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude," a short piece from 1996 that the program notes state was made in honor of George Balanchine, for five dancers and set to classical Franz Schubert. Here Forsythe seemed to be making a statement about classical, allegro ballet with all its virtuosity and flair. The movement, in keeping with the music, was quick, but almost too quick; it seemed like allegro gone wild. All steps were from the classical ballet vocabulary – soaring leaps, fast turns, nimble-footed jumps – but something was just off, slightly askew. The dancers' lines seemed imperfect, but consciously so. An arm would not be fully extended out, but would be held out at a kind of half-mast, a turn or a pose would be slightly off-balance. The dancers all smiled, but their smiles looked intentionally plastic, fake. The costumes — tutus but starched so that they almost looked Space Age — echoed this classical gone awry leitmotif. The last piece of the evening, "In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated," from 1987, is perhaps Forsythe's most famous work – and understandably so, as it constantly surprises, even thrills with its sharp contradictions. Set to harsh, but rhythmically percussive techno-industrial music by Thom Willems, the dancers performed, by turns, alone, in pas de deux, and in groups, but almost never in sync with each other. It was as if each dancer had his or her own choreography, each was dancing to his or her own drum. Whereas in classical ballet, a pas de deux would take center stage and all other dancers merely framing the central pair, here a duet would be simply one of the many actions going on onstage at any given time. Both movement and music created a sense of chaos, a cacophony, but an enthralling one. The movement was also a rather chaotic combination of classical and modern. At times, dancers simply stood at the back of the stage making various poses, some holding their arms in a classical port de bras, some in a more squarely modern form, some even in an exotic, Middle-Eastern-looking style. The visual effect was interesting, because, if one looked at the line of dancers long enough and deeply enough, one began to see that, through the unevenness, there was shape. Unexpectedly, the initial harsh clanking and shrillness of the music turned out to be very danceable, as a dancer raised her leg into a develope but in sharp staccato increments, perfectly in time with the techno beats of the music. The pas de deux were fraught with tension and frustration, sometimes with sexual overtones. Mikhail Lobukhin stood out here, adding an exciting virility and mischievousness to his partnering. In contrast to classical ballet, where a male dancer lifts a female romantically, far above his head, with all audience eyes on her, here the men here seemed barely to help the women; they seemed to work against the women, making the women nearly lift themselves into the air and hold themselves there. It was as if Forsythe wanted to illuminate the reality of ballet – that movement is incredibly athletic and fraught with difficulty and even danger; that women work just as hard as the men during the lifts and are not simply weightless china dolls tossed about with ease. The piece ended abruptly, as if right in the middle of something. As with each ballet on the program, you desperately wanted it to keep going.

Uliana Lopatkina & Daniil Koruntsev, Raymonda Photo © & courtesy of The Mariinsky Theater |

|

Corps de Ballet, La Bayadere Photo © & courtesy of The Mariinsky Theater |

|

Corps de Ballet, Chopianiana Photo © & courtesy of The Mariinsky Theater |

|

Uliana Lopatkina, The Dying Swan Photo © & courtesy of The Mariinsky Theater |

|

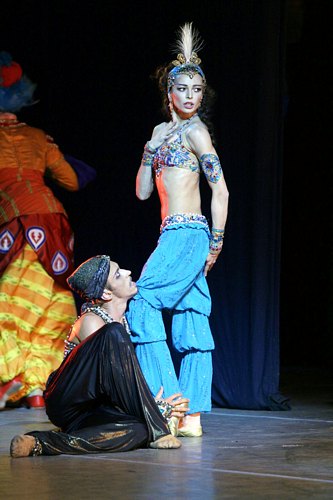

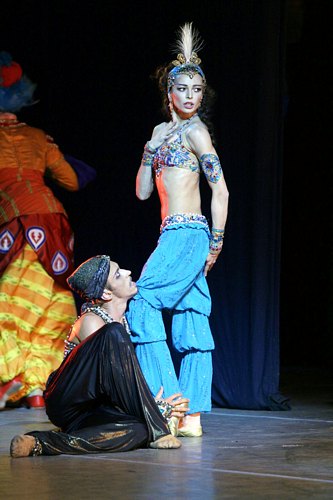

Diana Vishneva & Igor Kolb, Scheherezade Photo © & courtesy of The Mariinsky Theater |

|

Diana Vishneva & Andrian Fadeev, Rubies (from Jewels) Photo © & courtesy of The Mariinsky Theater |

|

Uliana Lopatkina, Le Corsaire Photo © & courtesy of The Mariinsky Theater |

|

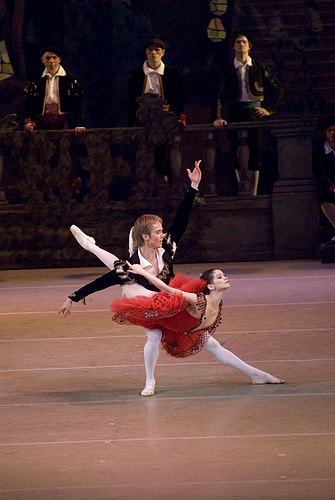

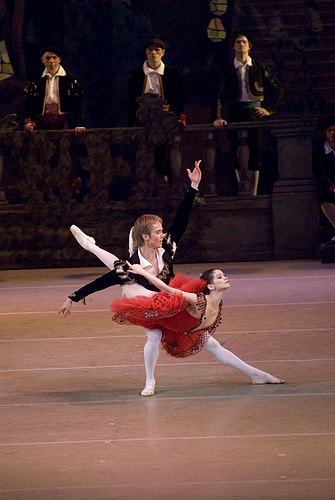

Leonid Sarafanov & Olesya Novikova, Don Quixote Photo © & courtesy of The Mariinsky Theater |

|

Irina Golub & Maxim Zyuzin, The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude Photo © & courtesy of The Mariinsky Theater |

|

Diana Vishneva & Igor Zelensky, Ballet Imperial Photo © & courtesy of The Mariinsky Theater |

|

|

|