|

|

|

|

|

|

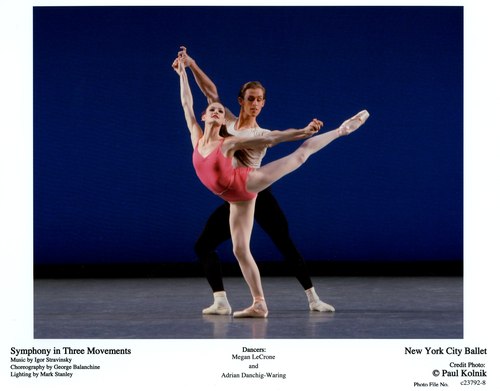

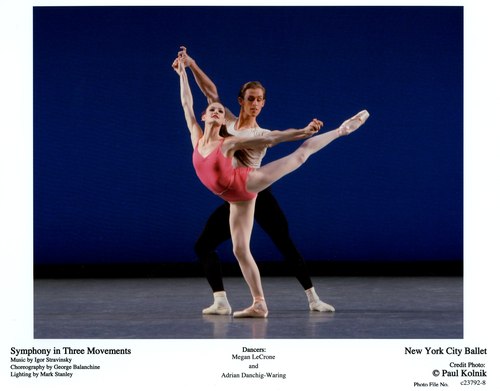

The ballet music for Walpurgisnacht Ballet was written by Charles Francois Gounod in 1869, ten years after he composed his initial version of the opera "Faust". It represents the occasion of hellish Mephistopheles introducing Faust to the revelries of the spirits of the dead on May Day Eve, Walpurgisnacht. Balanchine's 1975 choreography (he choreographed various productions of the opera in the twenties, thirties, and forties) isn't scary. Nobody dances as Satan's lieutenant or the challenged, self-righteous Faust. The music is, for the most part, rather innocently beautiful and undramatic. Only the frenzied final passage brings to mind Bald Mountain demons. Balanchine choreographed musical themes, rather than characters, and though the ballerinas all appear with their hair down and disheveled for the pounding, witch-flying movement, they begin the ballet and dance most of it in their pale tutus with their hair up. Ask la Cour and Sara Mearns dance their pas de deux and solos with wonderful brio. Ask la Cour is given a chance to show off his skill and strength here – he is sometimes hidden among others in the repertory. But here, he is a strong soloist and a careful partner. Ana Sophia Scheller – in a jeweled bodice (Barbara Karinska worked with Balanchine on these things, so it is as he wanted it) is elegant and commanding. These three dancers brought an explosive response from the audience – good, good work. Other featured dancers were Alina Dronova and Rachel Piskin, and in pas de quatre, Saskia Beskow, Amanda Hankes, Glenn Keenan, and Gwyneth Muller. Liebeslieder Waltzer is a favorite, a sumptuous, satiny ballroom dream to watch; it is also a formalized, patterned battle of the sexes interpreted through Balanchine's take on mid-19th Century social dances. The Johannes Brahms liebeslieder (love songs) are performed by pianists Richard Moredock and Susan Walters and fine quartet of singers: Nancy Allen Lundy, soprano, Jennifer Rivera, mezzo-soprano, Brian Anderson, tenor, and Jan Opalach, bass-baritone. The choreography for four couples – only eight dancers for the entire, long ballet – is also very demanding. Dancers are Darci Kistler, Kyra Nichols, Rachel Rutherford, Wendy Whelan, Jared Angle, Nickolaj Hubbe, Nilas Martins, and Philip Neal. Every one of the 32 waltzes is complex. The first act of the ballet, Opus 52, composed in 1869, comprises 18 waltzes and is danced by the men in black tie and tails, with the women in ball gowns and heeled dancing slippers. This is the more sedate act, but the more impishly choreographed, a sweet satire on popularity and competition. The curtain lowers, and the women return in tulle tutus for the 14 waltzes of Opus 65 (composed in 1874), with full-out, difficult dancing. This act, according to Balanchine, differs from the first in that the first act was the "real people dancing" whereas in the second act, it is their souls. Their souls dance their hearts out. There are gems of partnering here, challenging to describe: a woman in arabesque whose partner, embracing her, lowers her nearly to the floor, so that her supporting leg is brought parallel to and nearly resting on the floor, while the trailing leg closes, then that (the trailing) toe, arched strongly and still en pointe, takes the weight, as she arcs the leading leg along the floor until the leading toe plants and her partner again raises her slowly upright to repeat the arabesque, and this scalloped stride repeats again and again. The men are given little solo work in this ballet. Balanchine's dictum: "woman is dance." Rachel Rutherford, who has only been a soloist since 2002, is new to this ballet, and dances with secure grace and understanding of the ballet. Many of the other dancers have been on the scene a long time, and some have indicated they'll be moving on, either to other positions with NYCB or elsewhere. Wendy Whelan has been with NYCB for 21 years. Kyra Nichols has had the longest career ever with the NYCB – 33 years, since 1974 – and will leave at the end of this season. Darci Kistler has been with NYCB for 25 years and now teaches at the School of American Ballet. Nikolaj Hubbe will soon leave to be director of the Royal Danish Ballet. Messrs. Angle, Martins, and Neal have already had respectable careers here, and it is hoped they will stay for a very long time. Such a demanding ballet must welcome some of the "deep bench" of fine dancers from the NYCB corps of the School of American Ballet. Symphony in Three Movements is performed to Stravinsky music, none of it composed specifically for ballet. It is a large ballet, whose very largeness made it hard to take in after the earlier dances. The music is a dash of bitters after the rich Brahms. In the first movement, three couples, Tiler Peck (dancing in place of Ashley Bouder) and Tom Gold, Megan LeCrone and Adrian Danchig-Waring, and Abi Stafford with Albert Evans, brought excitement to the angularity of the choreography. There are 27 other dancers onstage, all of whom were also completely focused on the piece and on the count. The second movement, however, a pas de deux with Abi Stafford and Albert Evans, is the core of the dance – think flexed feet instead of arched, think cleverness over grace – but think too that it still works as ballet, just with jazz for a soul. The third movement brings the entire cast back onstage. This is a convincing, accomplished, and thoughtfully made dance and performance. It is, however, difficult to love. Balanchine's choreography is represented from many decades – Walpurgisnacht, though first performed in 1980 by NYCB, had a three-decade long gestation during the early part of the 20th Century; Liebeslieder has its premiere in 1960; and Symphony in Three Movements had its premiere in 1972. If there is an essential Balanchine, it – the work – must be understood along the time and space continuum. Each iteration is essential viewing.

Megan LeCrone and Adrian Danschig-Waring in NYCB's Symphony in Three Movements Photo © & courtesy of Paul Kolnik |

|

Kyra Nichols and Nilas Martins, Wendy Whelan and Nikolaj Hübbe in NYCB's Liebeslieder Walzer Photo © & courtesy of Paul Kolnik |

|

|

|