|

|

|

|

|

|

Like the prodigal child returned, the New York City Ballet came again to Chicago after a quarter century absence. And like the parent of the long-missed child, Chicago welcomed the company to the recently conceived Harris Theater, the city's dedicated dance performance space, proof that audience and demand exist for this caliber of world-class dance. Divertimento No. 15 (1956): Music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (K.287), Choreography by George Balanchine, ©The George Balanchine Trust, Costumes by Karinska, Lighting by Mark Stanley, Guest Conductor: David Briskin, Performed by Yvonne Borree, Megan Fairchild, Sterling Hyltin, Abi Stafford, Miranda Weese, Edwaard Liang, Jonathan Stafford, Andrew Veyette, and the Company. Melodious and courtly in tone and musical form, like the original type of light dance entertainment popular with 18th century aristocrats, Balanchine's movements nonetheless, bear his unmistakable maker's mark. The bare stage with its clear blue background popped against black velvet drapes and created a feeling that the dancers were gamboling about in the countryside, perhaps gathered for a picnic and other light-hearted fun. Karinska's original costume designs emphasized the sense of bucolic playfulness. As my guest, Paula Drake of Tutus Divine ( see interview ExploreDance.com, July 16, 2005) noted after borrowing my binoculars for a closer look, "I love the way the New York City Ballet does their skirts. Very seldom do they use hooping. The soft bell tutu has more movement and softness to them." In this work, "…horsehair braid on the tutus gives them the layered look…" and "…spring colors Karinska used…" also created a pastoral sense of place without benefit of scenery. One pas de deux in particular reminded me of a shepherd and his love (though not as completely clothed as these dancers), who, as they flee from a sudden storm, turn their faces upwards, to bask in the sunshine that follows Through the movements of Allegro, Theme and Variations, Minuet, Andante, and Finale, the soloists performed quintessentially classic balletic movements but with an edge. Angles emphasized by leg extensions in one direction and opposing head movements and direction-changing turns reminded me that Balanchine was using the old divertimento form in a new way, which would later be seen at greater length in his risk-taking Jewels. In the Night (1970): Music by Frédéric Chopin, Choreography by Jerome Robbins, Costumes by Anthony Dowell, Lighting by Jennifer Tipton, Pianist: Cameron Grant, Performed by Rachel Rutherford, Tyler Angle, Maria Kowroski, Charles Askegard, Jenifer Ringer, Sébastien Marcovici, Production made possible by Mrs. Thomas J. Hubbard. Set against a starry backdrop, three couples appeared, each in their own turn, gliding through the night in one another's arms. The women wore waltz-length floaty skirts, double layered with lighter colors shaded by a darker overlay. With every step, turn, lift, carry, the tulle wafted behind them producing an after-age effect, or one of dreamy lassitude. The first pas de deux lingered over a slow adagio and made the audience the voyeur to the longing and physical chemistry exuded by Rachel Rutherford and Tyler Angle. Dressed in shades of mauve, the color hinted at the purple hour of night when lovers seek their beloved in intimacy that excludes all else. Well matched in physicality and appeal, they personified harmony in relationship. Maria Kowroski and Charles Askegard as the second couple were teasing and playful. Costumes in rusty ochre tones evoked a Russian esthetic, as several poses reminded me of choreography in Petrouchka with heel jabs and spread hands framing faces. This pair was challenged to test their trust in one another with unexpectedly divergent lifts. Several times Askegard caught Ms. Kowroski in a modified fish dive and carried her at his hip, parallel to the ground, like a suitcase, her feet flipping as though she were swimming. I'd seen this feat only once before, (though without the foot movement) when the Eifman Ballet performed Anna Karenina. However, it was the upside down vertical lift held for a long count of ten done once, then again, to make the point of being what? Head over heels? Giving oneself over entirely to a partner? This produced the biggest "wow" factor. The last pair, Jenifer Ringer and Sebastien Marcovici, was the on-again-off-again couple. The flame color of the inner skirt of Ms. Ringer's costume was the visual embodiment of the heat at the core of their relationship. She rejected him. Grew angry. Received the benison of his nurturing touch cradled in his arms, and back and forth in a stew of conflicting emotions. Their pas de deux required the most acting to tell their story and Ms. Ringer played her role as well as she danced her steps. Ultimately, the three couples encounter and acknowledge each other, briefly changing partners for a few steps only to return to their original mates and drift off into the darkness in what Paula termed, a "seamless performance." The Four Temperaments (1946): Music by Paul Hindemuth, Choreography by George Balanchine, ©The George Balanchine Trust, Lighting by Mark Stanley, Conducted by Maurice Kaplow, Piano solo by Nancy McDill, Performed by Faye Arthurs, Adrian Danchig-Waring, Amanda Hankes, Amar Ramasar, Tom Gold, Jennie Somogyi, Charles Askegard, Albert Evans, Teresa Reichlen and Ensemble. Imagine believing, for want of more accurate scientific knowledge, that one's body and moods are affected by four elements in the body. Those four humors, as they were called, ruled one's nature and if they were out of balance, caused a person to behave in extremes. For instance, too much blood caused willfulness and heated emotions, whereas an excessively phlegmatic individual was emotionless and passive. Using the humors as the framework for the four movements of the ballet, the dancers kinesthetically portray the characteristics of a body out of synchronicity with its elements. In the Melancholic, Sanguine, Phlegmatic, and Choleric variations, the dancers, clothed in simple practice wear of leotards, tights and white lycra tees, are like so many little cells of the body busily going about their tasks. Signature movements, such as arms angularly entwining, cradled rocking, and carrying off stage, with the female held in an L shape, legs extended at a right angle and braced against her partner's body, all piqued my interest with their inventiveness. Moving crisply and precisely during each of these movements, the ensemble pulsed with the energy of a vital force within a living being. I'd been told twice during the week by people who hadn't felt well, that going to the ballet made them feel better. There could only be agreement after my afternoon with the New York City Ballet, especially thinking that so far, this had been a once-in-a-lifetime experience. I hope I won't have to wait another twenty-five years to see more of the seventy-five work repertoire they maintain.

Founders, George Balanchine and Lincoln Kirstein Founding Choreographers, George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins Ballet Master in Chief, Peter Martins Resident Choreographer Christopher Wheeldon, Composer in Residence, Bright Sheng Ballet Mistress, Rosemary Dunleavy Children's Ballet Master, Garielle Whittle Children's Ballet Mistress, Kathleen Tracey New York City Ballet Orchestra Music Director Designate, Fayçal Karoui Principal Conductor, Maurice Kaplow Guest Conductor, David Briskin Conductor Emeritus, Hugo Fiorato Press Coordinator, Jill Evans

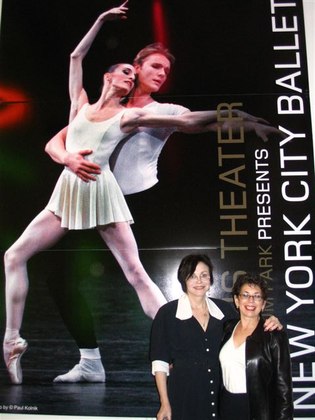

Paula Drake of Tutus Divine at the NYCB Photo © & courtesy of Susan Weinrebe |

|

Paula and Susan at the Harris Theater Photo © & courtesy of Susan Weinrebe |

|

Paula and Lauren Outside the Harris Theater Photo © & courtesy of Susan Weinrebe |

|

|

|